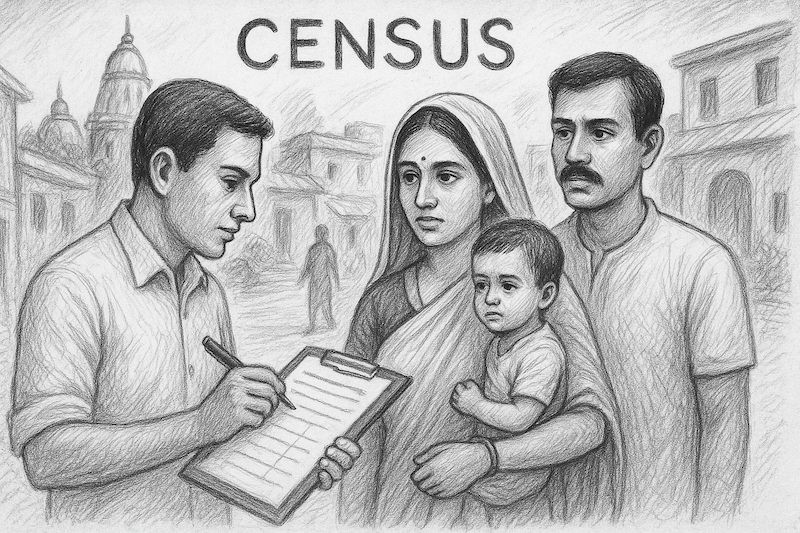

The Story So Far: A Historic Delay and a Transformative Moment

The Indian government has officially announced that the next Census will be conducted in two phases, with March 1, 2027, as the reference date. This is the first time since 1881 that India will witness a break of over 10 years between two censuses — the last one being held in 2011. The interruption was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but postponements have continued well into the decade due to the sensitive and complex nature of the upcoming exercise.

Unlike earlier censuses, this one isn’t just about counting people. It is set to reshape India's social and political architecture — through the inclusion of caste enumeration, its use in parliamentary delimitation, and the basis for implementing the Women’s Reservation Act.

A Long History of Counting the People

India’s tryst with population data goes back centuries — with references in Arthashastra and Ain-i-Akbari showing how rulers recorded demographics for taxation and governance. The first synchronous Census in modern India was held in 1881 during British rule, under the leadership of W.C. Plowden. Since then, every Census (barring the 2021 one) has taken place every 10 years, evolving in scope and depth.

Before Independence, the Census also recorded caste details. However, after 1947, only Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) were officially counted. The last time caste for the entire Hindu population was included was in 1931. Now, after nearly a century, India is poised to revive full caste enumeration — a move with profound social and political implications.

How the Census Is Conducted: Two Phases of Enumeration

Census operations in India are governed by the Census Act, 1948, and fall under the Union List of the Constitution, giving the Central government sole authority to carry them out. A Census Commissioner is appointed by the Centre to oversee the exercise, while Directors of Census Operations manage the process in each state. However, the actual field work is largely conducted by state-appointed staff, mostly schoolteachers.

Since 1971, the Census has been conducted in two distinct phases:

-

House Listing Phase: Conducted over 5-6 months, it collects data on housing quality, amenities (water, electricity, toilets), and household assets like TVs, computers, and vehicles. In 2011, this phase included 35 questions.

-

Population Enumeration Phase: This is held close to the reference date (usually March 1) and gathers individual information on name, age, gender, religion, language, education, occupation, and SC/ST status. The data is compiled into a provisional report within weeks, while the detailed final report is released about two years later.

Why the 2027 Census Is So Important

Three major factors make the upcoming Census extraordinarily significant:

1. Caste Enumeration:

For the first time since 1931, caste data for all Hindus will be recorded. This comes in response to strong demands from political parties, civil society groups, and state governments. The data is expected to serve as a basis for revisiting policies on affirmative action and social justice — especially regarding OBCs (Other Backward Classes).

2. Delimitation Based on New Population Data:

The 2027 Census will be the first to be conducted after the 2026 deadline for revisiting seat allocation in Parliament and State Assemblies. Since 1971, the number of seats in the Lok Sabha and state legislatures has been frozen to avoid penalising states that successfully controlled population growth. This freeze is now set to end.

If new seats are allocated strictly by population, northern states with high growth may gain more representation, while southern and northeastern states that have stabilised population could lose political influence. This is a major concern for federal balance.

3. Implementing Women’s Reservation:

The recently enacted Women’s Reservation Act mandates reserving one-third of seats for women in Parliament and State Assemblies. However, it will be implemented only after the next Census and delimitation. Thus, the 2027 Census becomes the trigger for greater gender representation in Indian politics — a long-awaited step.

Apprehensions of Southern and Smaller States

States such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and those in the northeast have voiced serious concerns. Their apprehension is not about being counted — but about being politically sidelined if the number of seats in Parliament is re-allocated solely based on population. These states have invested heavily in health and education, achieving lower fertility rates and stable populations.

They fear a scenario where states with higher population growth — often due to poorer social indicators — may gain disproportionate power in Parliament, undoing the federal equity envisioned in the Constitution. Many are calling for a freeze on seat allocation or a balanced formula that rewards development alongside population size.

The Delay and Its Consequences

The decade-long delay has already impacted policy planning:

-

Welfare schemes like the Public Distribution System (PDS), which rely on household counts, may be misaligned with current ground realities.

-

Urbanisation, migration, and occupational shifts remain underrepresented in the absence of new data.

-

Affirmative action policies, particularly for OBCs and EWS categories, still depend on dated figures.

A timely and efficient Census would provide the evidence base to revise allocations, redistribute resources, and reform electoral boundaries in a data-driven manner.

What Lies Ahead: The Way Forward

For the Census to fulfil its promise:

-

Caste enumeration must be carried out with scientific precision, avoiding duplications and omissions.

-

Wide consultation with states must precede any delimitation, ensuring that democratic equity and federal balance are preserved.

-

Gender data must be incorporated in a way that genuinely empowers women’s political participation.

-

Technological upgrades (such as digital data collection and biometric verification) can improve accuracy and speed.

-

And above all, transparency and public trust must be maintained throughout the exercise.